Panama’s National Authority for the Environment (Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente, ANAM) manages Coiba National Park, which is accessible via permit. Guests can book overnight lodgings in several air-conditioned cabins next to the ANAM ranger station.

Paul Henderson Photography/Getty Images

When Ezer Vierba first visited Panama’s Coiba Island in 2004, the history teacher at Boston’s private Winsor School was shocked by its size. At 194 square miles, Coiba is the largest island in Central America. A huge swath of largely tropical forest covers 80 percent of the island, which is also brimming with white sand beaches, gushing waterfalls and thermal hot springs, and surrounded by clear, fish-filled waters sporting a ring of protective coral reef—one of the largest in the eastern Pacific Ocean. “As a tourist attraction,” says Vierba, “quite frankly, it’s gorgeous.”

But Coiba also has a dark side, and that’s what Vierba, who has a PhD in Latin American history, had come to see.

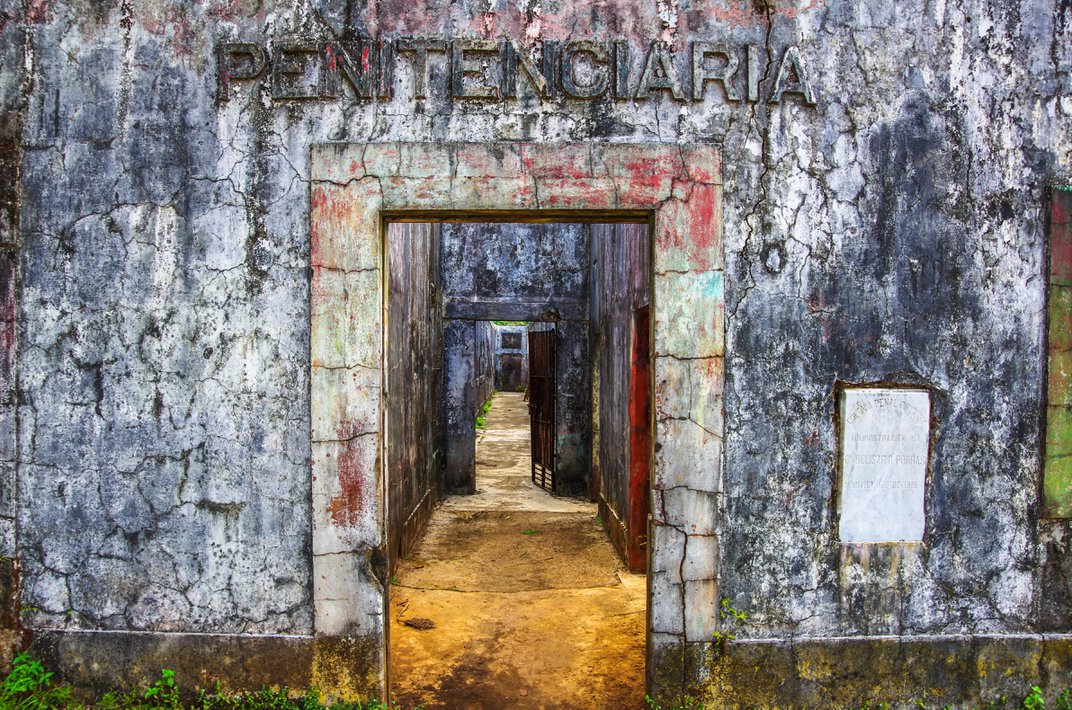

From 1919 until 2004, Coiba Island was home to some of Panama’s most dangerous murderers and rapists, as well as thousands of politcal prisoners dubbed “los desaparecidos” (“the disappeared”) who went missing under the dictatorships of Omar Torrijos and Manuel Noriega. The remoteness of the island—Coiba disconnected from the mainland more than 12,000 years ago, due to rising sea levels, and its last known Indigenous inhabitants left in the mid-1500s—made it an ideal place for establishing an early 20th century penal colony, where prisoners are sent to live and work under forced labor. It was difficult to reach, and even tougher to escape from.

The remoteness of Coiba Island made it an ideal place for establishing an early 20th century penal colony. Urs Hauenstein/Alamy

Coiba housed as many as 1,300 prisoners, the bulk of them living in 30 or so agricultural camps spread around the island. “The camps stood so far apart,” says Vierba, “that you couldn’t get by foot from one to another.” In fact, Coiba was the world’s largest island prison after Australia, which served as a penal colony in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Penal colonies were once prevalent throughout the Americas, and it seemed the more isolated, the better. There was one…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Travel | smithsonianmag.com…