A gray afternoon in winter is not usually considered the best time to visit a garden, but it’s perfect for my first glimpse of this extraordinary place. A battered sign reads: “Positively No Admittance!” Paul Orpello, my guide, opens a creaky gate and leads me into a landscape of ruins, which was largely abandoned for more than 50 years and is now being brought back to life. I realize that “garden” isn’t the right word for it. It feels more like a magical lost city that was bombed in a war.

Orpello guides me past murky former swimming pools that now hold snakes and sludge. We sidestep sinkholes and rubble piles. We pass a terrace of cracked columns and crumbling brick walls with hidden recesses like tiny witches’ caves. It feels like traversing the fire swamp in The Princess Bride, risking quicksand and Rodents of Unusual Size. Despite being buried under weeds for decades, a swan mosaic is almost perfectly intact. This may be the strangest garden in America, at once the darkest and most joyous, unlike any other place I’ve been. Orpello tells me that what he’s experienced in this garden changed his life.

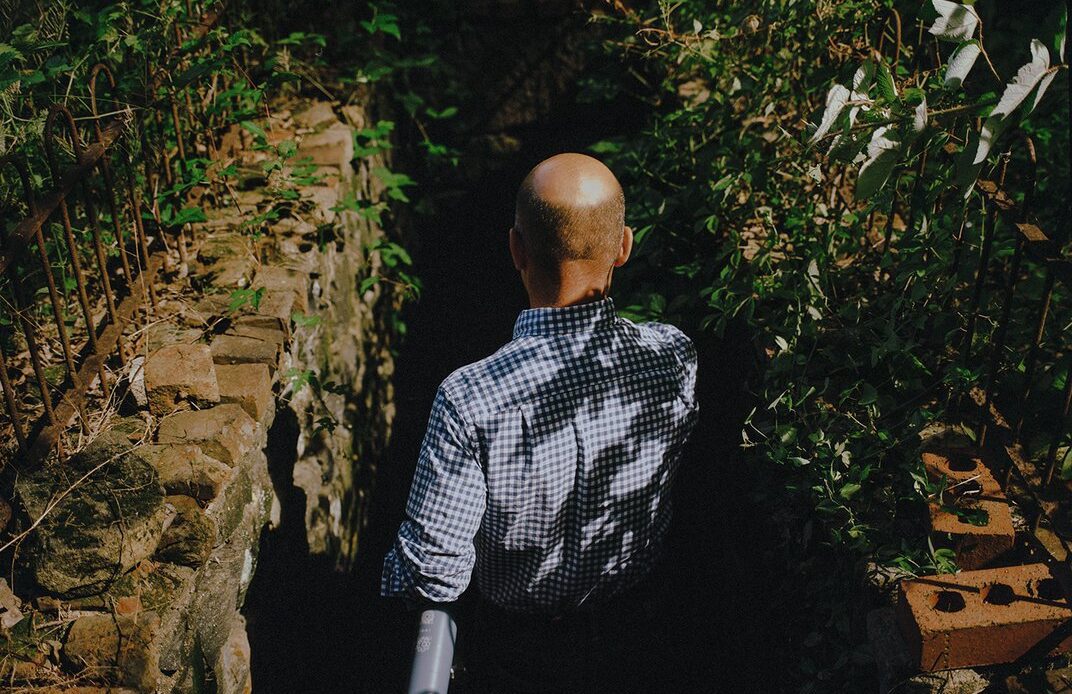

Paul Orpello, director of gardens and horticulture at the Hagley Foundation, descends from the Refinery Terrace to the Azalea Terrace in the Crowninshield Garden.

Sasha Arutyunova

A staircase leads from the Cistern Terrace to the Refinery Terrace. Sasha Arutyunova

Walking these paths evokes even more powerful feelings after one learns the landscape’s poignant history. For over a century, the du Pont family operated a black powder mill here in Wilmington, Delaware, where more than 300 workers combined saltpeter, charcoal and sulfur to create the explosive powder used in mining and construction—and munitions during wartime. It was dangerous work, and during the years the mills operated, from 1802 to 1921, there were 288 accidental blasts, which killed 228 people, mainly workers. The most powerful came on a foggy afternoon in October 1890, when over 100,000 pounds of black powder detonated, collapsing seven buildings. The…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Travel | smithsonianmag.com…