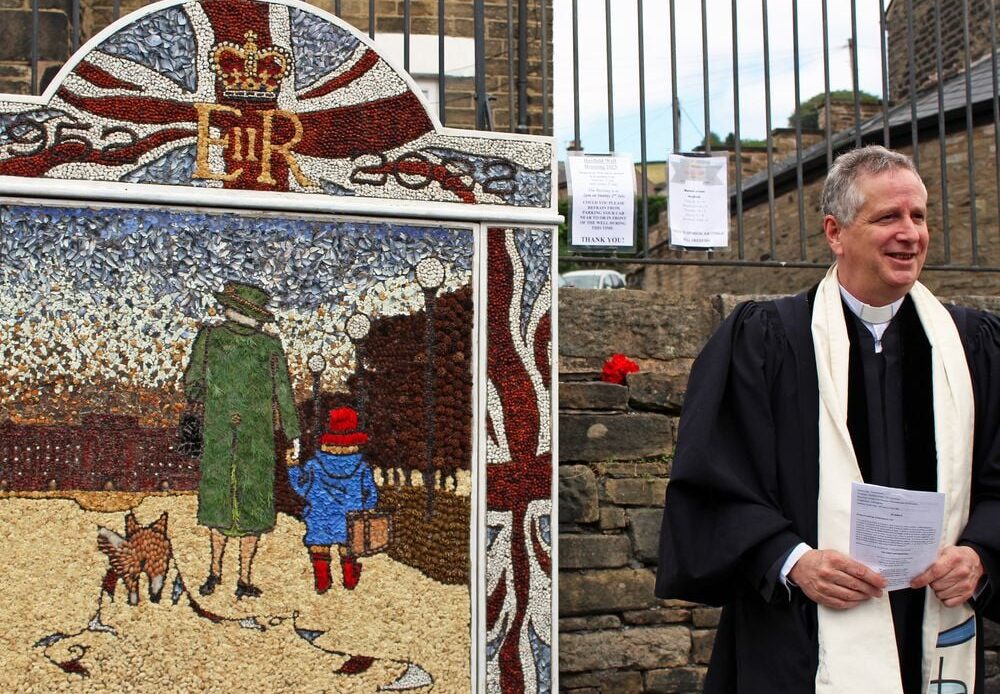

This Queen Elizabeth II well dressing took eight people over 35 hours to create in late June in Hayfield, Derbyshire, England.

Vicky Smith

Her hair is a wad of sheep’s wool, like the tail of the corgi at her heel, and she wears a long emerald coat made of leylandii, an evergreen that makes for a common hedge in the United Kingdom. A petaled Paddington Bear holds her hand—his hat and wellies made of vibrant red gerbera, his coat blue hydrangea—and they walk along a path of dried chamomile flowers.

If this portrayal of the late Queen Elizabeth II sounds unusual, that’s because it’s a well dressing. From May to September, over 80 communities across England’s Peak District (and a little beyond) create these spectacular natural pictures before placing them by wells and water features.

The mysterious tradition is often linked to the village of Tissington in Derbyshire, where it’s thought residents first started decorating their wells to give thanks for fresh water—either in 1348, when they believed their pure source saved them from the Plague, or during a drought in 1615, when the trusty font continued to run. The origins can’t be traced any earlier, art historian Rosemary Shirley at the University of Leicester points out in an essay in the journal Landscape Research, though “some commentators speculate on possible Roman or pagan beginnings.”

From May to September, over 80 communities across England’s Peak District (and a little beyond) create these spectacular natural pictures before placing them by wells and water features. Vicky Smith

Once simple garlands and wreaths, dressings later became the intricate artworks we see today. In an evocative description of how these are made, Shirley writes:

“Each spring, a week or so before Ascension Day [a Christian holiday commemorating Jesus Christ’s ascension into heaven, celebrated 39 days after Easter Sunday], large timber boards, shaped like Gothic church windows, their surface knobbled with the heads of large nails, are dropped into the village pond, where they float, soaking up the brown water until their grain is saturated. Clay, dug from a seam in one of the local fields, is pounded with feet until it is sticky and malleable enough to push into the boards, the nail heads giving some…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Travel | smithsonianmag.com…