At the top of Mount Hamilton, near San Jose, Calif., Lick Observatory looks out over the dense sprawl of the San Francisco Bay Area. On a clear day from the 4,200-foot summit, you can see San Francisco to the north, as well as the entrance to Yosemite Valley, 120 miles east, as the crow flies. At night you can see even farther — millions of light-years into space.

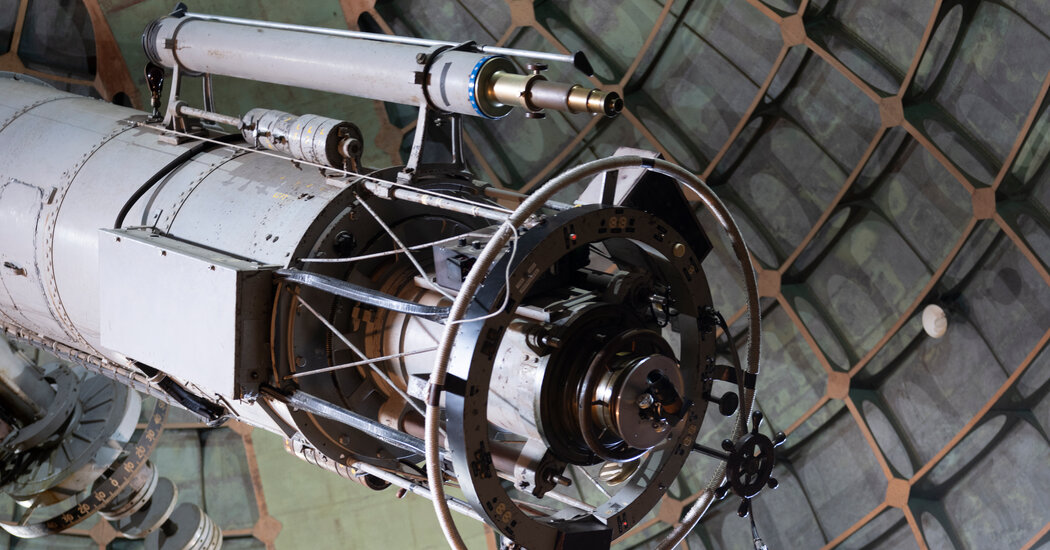

When it was completed in 1888, Lick (named for its sponsor, James Lick) boasted the best telescopes and best year-round conditions of any observatory in the world. Its white domes were beacons for astronomers and visiting dignitaries, as well as hundreds of curious locals who made the long journey up the mountain each weekend.

Now, Lick Observatory is one of only a few remaining historic observatories still open to the public in the United States. Contemporary funding prioritizes ever-larger telescopes in dark, dry, high-altitude sites, like Chile’s Atacama Desert, or space-borne telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope. Theirs are the extraordinary discoveries that regularly make the news. But historic observatories still have wonders to share with visitors and astronomers alike.

Lick Observatory and Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., which opened in 1894, both remain active in astronomical research. Other historic observatories now focus primarily on public outreach and education, including Yerkes Observatory (1897) in Williams Bay, Wis., and Mount Wilson Observatory (1904), outside Pasadena, Calif. At each of these sites, you can step into the history of the cosmos — experiencing the deep time of the stars, as well as more recent histories of discovery.

Looking through 19th-century glass at the Lick, you can see where E. E. Barnard spotted a new moon of Jupiter and James Keeler found a gap in Saturn’s rings. At Mount Wilson, Edwin Hubble, building on work done by Henrietta Swan Leavitt at Harvard, made an observation that proved there were other galaxies in the universe beyond the Milky Way. At Yerkes, you can peer through the 40-inch refracting telescope that surpassed Lick’s in size in 1897 and was used by a cadre of path-breaking women working in astronomy.

As the artist Aspen Mays and I prepared to visit Mount Hamilton this fall, she reminded me of yet another layer of time we would be traversing on our trek up the mountain: the white domes that now stand as accidental monuments to anthropogenic change. In the valley below the Lick,…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at NYT > Travel…