This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

When Ada Blackjack arrived on Wrangel Island as part of a 1921 polar expedition, she knew nearly nothing about Arctic survival.

She had never built a house or shelter. Guns and knives terrified her, as did polar bears. And she had never stored provisions or trapped small game.

Despite a lack of essential skills, she braved the harsh conditions of the far north — desperate to earn money for her son’s tuberculosis treatment — and remained alive by sheer force of will.

She had been hired as a seamstress to accompany a crew organized by the Arctic explorer Vilhajamur Stefansson, who sought to claim the desolate island between Alaska and Russia for the British Empire.

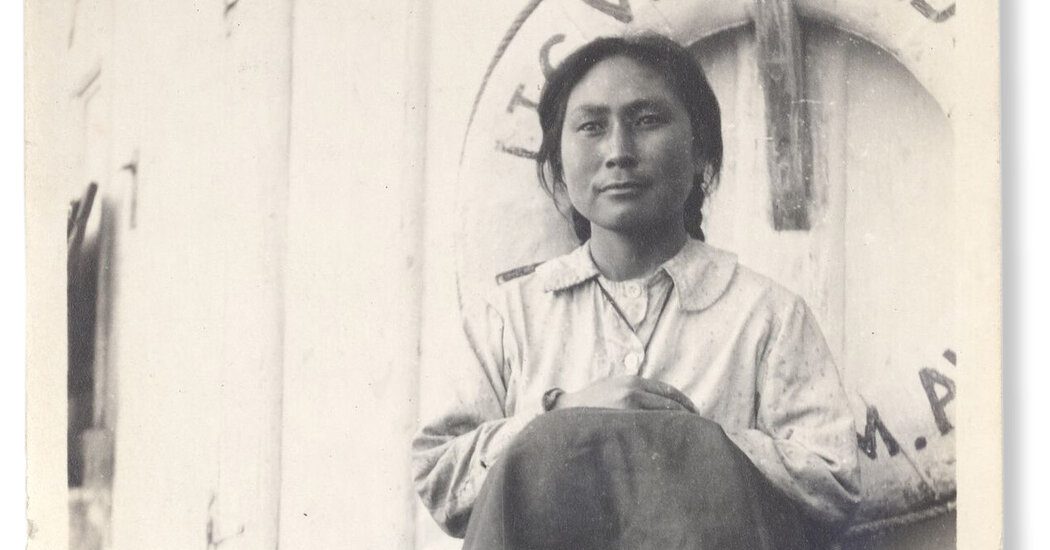

But more than two years after the party was marooned on that barren speck of land, a rescue operation found Blackjack to be the sole survivor of the Wrangel Island expedition.

“Filling in the gaps between her terse, reluctant sentences, one pieces together the stern truth,” read a Los Angeles Times article in 1924. “The stronger, bigger white men died because they were not fit — in the biological sense — to survive. There was game, but they did not know how to catch or kill it.”

Woefully ill-prepared and undersupplied, three of the venture’s young men left their base on the island in an attempt to cross over sea ice to Siberia and seek help. They were never heard from again.

A fourth man, gravely ill with scurvy, was put in Blackjack’s care until he died.

Left to fend for herself, she learned to conquer the elements. She lugged firewood for miles, killed foxes, built an umiak and made a parka out of reindeer skin.

Upon her return, the press heralded her as the “female Robinson Crusoe” and followed her every move. But Blackjack took a humble view.

“In later years, when people called her brave, she would tilt her head to one side and gaze at them, unblinking, with dark brown eyes,” an article in The Denver Post recounted in 1973. “After some time, she would answer simply: ‘Brave? I don’t know about that. But I would never give up hope while I’m still alive.’”

Ada Delutuk was born on May 10, 1898, on an Iñupiat settlement in Spruce Creek, Alaska. Her father died when she was 8, and her mother entrusted her to the care of Methodist missionaries in nearby Nome, who taught her math, reading and writing, in addition to doing…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at NYT > Travel…