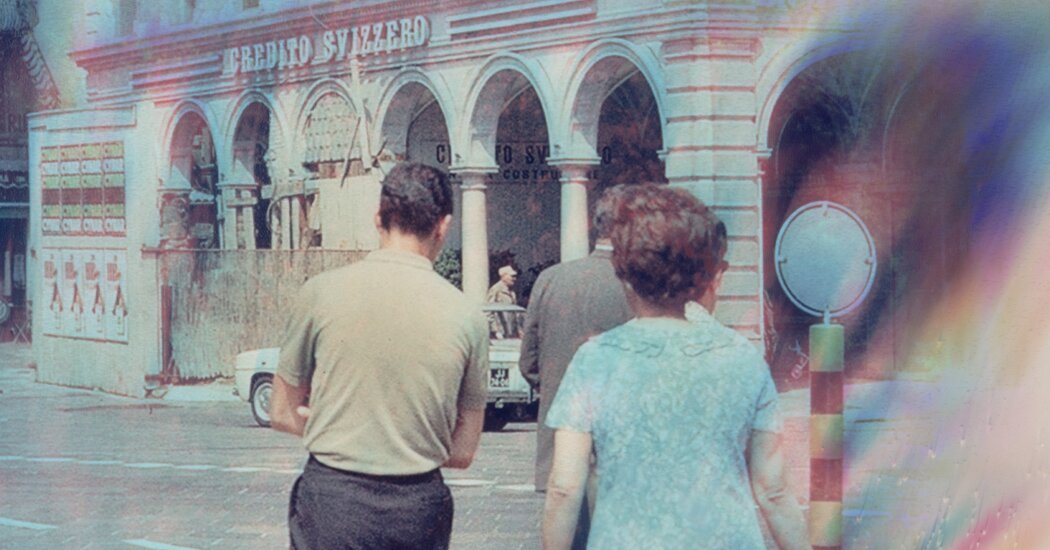

When I was growing up, my dad, who has left the country only a few times, told me about the trip to Europe he took with his parents when he was 14, in 1966. He told me how much Nonie loved the immaculate Swiss streets and window boxes fizzing with flowers; the fireplace in the hillside home outside Lugano, where his father was born, with clever alcoves on either side for drying clothes or warming bread; the palpable poverty of the home in Pozzuoli, a city just outside Naples, where Nonie’s aunt lined her walls with newspaper to add insulation. Every so often, my father would drag out the projector and show me his Kodachrome slides.

As an adult, I spent years telling him that he and I should repeat the trip together — or at least a short version in which we went to Switzerland and Italy, Lugano and Naples, so he could show me where his family was from. But now that his Alzheimer’s was progressing, that proposal had taken on new significance. Revisiting the past would, I hoped, help him live better in the present. A few years ago, I read about a palliative treatment for those with memory disorders, called reminiscence therapy. The therapy involves triggering the participants’ strongest memories — those formed between the ages of 10 and 30, during the so-called memory bump, when personal identity and generational identity take shape. Reminiscence therapy can take many forms: group therapy, individual sessions with a caregiver, collaboration on a book sharing the patient’s story or just conversation between friends. But the goal is the same: to comfort, to engage, to increase connection — and to strengthen the bond between patient and caregiver.

One of the more immersive iterations of reminiscence therapy is a place called Town Square, an adult day care for those with dementia. I visited shortly after it opened in 2018. The day care consisted of an artificial village designed by the San Diego Opera to look like a town from the 1950s. It had a diner, beauty salon, pet store, movie theater, gas station and city hall. By replicating the time period during which participants’ brightest memories burned, Town Square hoped to improve their quality of life. The décor offered lots to talk about. A portrait of Elvis hung in the living room, for instance, and upon seeing it, a woman spoke of her teenage years, teleporting into her past. “There is no time machine except the human being,” Georgi Gospodinov writes in his novel “Time Shelter,” about a…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at NYT > Travel…